features

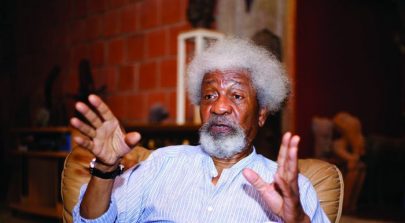

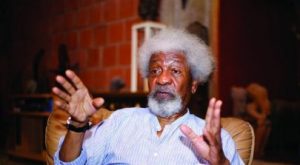

Buhari doesn’t have what it takes to govern Nigeria properly – Soyinka

Nobel laureate, Prof. Wole Soyinka has said that President Muhammadu Buhari does not have what it takes to govern a complex country like Nigeria properly.

Nobel laureate, Prof. Wole Soyinka has said that President Muhammadu Buhari does not have what it takes to govern a complex country like Nigeria properly.

Soyinka, in an interview with TheNEWS, when asked if Buhari had what it takes to govern Nigeria simply said ‘no.’

“No. Definitely no. Buhari cannot govern this country properly. That became clear during his first term in office. For a start, I don’t think he understands this nation. He’s incapable of grasping the complexities of a nation like Nigeria and because of that, he is trapped, among other governance derelictions, in the divisive snare of nepotism.

“It’s real. It is blatant. He goes so far as to pluck people from retirement for jobs or sensitive positions simply because they are the only people he knows and trusts. The pattern has remained consistent. In the last elections, I urged voters to abandon APC and PDP, since the latter was just as severely lamed, and try and install a fresh mind,” he said.

When asked what the nation could do to solve the insecurity problem, Soyinka said whether the nation liked it or not, there was something called national psychology, which everybody did not share.

“Whether we like it or not, there’s something called national psychology that, obviously, not everybody shares, or partakes of. But, collectively, when you assess it when you’re looking at collective social conduct, you find that one of the aspects of that social conduct is the national tendency towards mimicry, imitation– that person is doing it, I must do it — most of the time of a negative model. You will remember that I was pulled into the struggle of MEND – Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta– largely because of my association with Ken Saro-Wiwa who ended up on the gallows in the most horrible circumstances.

“I’ve always believed in the struggle of the Ogoni and indeed of the Niger Delta. Some of them would come to me to discuss their problems and seek advice. However, when they embarked on kidnapping, I told them bluntly that I was in total disagreement with such tactics, that they should never embark on that trend. I was one hundred percent certain that it would be taken over by the criminal elements among them to start with. And in any case, kidnapping and imprisoning other human beings as an option in any struggle for one’s own liberation is fundamentally flawed.

“But, in addition, it had the danger of creating a mimic industry in a nation like ours and, sure enough, that has happened. In fact, as a result of that my position which was made public, when some Americans were kidnapped for the first time in those early stages of what has now gone out of control, FBI operatives were sent to Nigeria to look into options for rescuing them, they actually asked to see me. The American embassy arranged a meeting. At that time, Asari-Dokubo’s wife was taking refuge with me in Lagos. In fact, that was one of the reasons I agreed to meet them. I introduced them to Mrs Asari-Dokubo and, through her, tried to contact her husband who was then in detention. Eventually, he and other detainees were released. How they were released, I have no idea, but anyway, I was able to facilitate the process simply because of the position I had taken,” he explained.

Soyinka lamented that from that beginning, had now sprung, as he warned, this now transnational industry in Nigeria, saying that to stop it now required the entire co-ordination of efforts across religion, business, rural governments, and the sensitisation of the entire nation towards the exercise of their powers of observation.

“For example, look at where hostages were kept in Lagos by the billionaire kidnapper, Chukwudumeme Onwuamadike, alias, Evans, for over a year, in the midst of a busy urban residential area. It requires the mobilisation of the entire populace on a level we have never known. It includes the involvement even of children-– they have, after all, become first-line victims. We should inculcate a sense of observation– virtually turning the country into the kind of security zone that operates at airports. Life goes on with seeming a normality but in actual fact under permanent watch. Only this time, it is like an effective neighbourhood watch. But it is in our own interest. Otherwise, this thing will proliferate into unmanageable proportions.

“Then also, I almost forgot, a decentralisation of the police. We need a centralised police presence, yes, as we do the military, but we also require a police force whose structures and operating members are part and parcel of the community. People talk to them more naturally because they live inside, and are known to the community. They themselves, of course, get to know the nooks and corners of their community and naturally develop a more acute sense of observation as they earn the confidence of citizen-informants in such a way that people understand, routinely, that it is service to themselves, service to their families, their children, relations or colleagues that they become observers and informants,” he said.

The Nobel laureate was also asked at what point the nation got it wrong. He said the nation got it wrong right from the first coup of 1966 which brought in the military.

“I think where we got it wrong was, first of all, the coup itself, which brought in the military. I think the military was largely responsible. That was when we lost it so to speak, and it’s important to admit that we are all to blame. When the military took the centralist road, many of us applauded, never mind that people like to deny it today. But for us at the time, we read it as the ending of ethnic divisions. For instance, before the military took over, regionalisation had created certain dimensions of narrow factionalism, but it was simplistic to think you could obviate all those unfortunate aspects of regionalisation by a sweeping centralism. That was disastrous thinking. But we’d become sold on this mission of eradication of “tribalism”, which we didn’t interpret properly.

“Everybody was guilty of it-politicians, intellectuals, bureaucrats, technocrats, students, etc., etc. Everybody wanted to become an amalgam called Nigerian, a non-existent being, the “detribalised being” and that centralist agenda looked as if it was the magic road. It deepened suspicions, retarded development; it created atop-heavy bureaucracy, distancing beneficiaries of policies from those who made the policies.

“Let us not omit the following, however: the departing British laid the foundation for future fissures by a deliberate strategy of distorting the power relations between North and South, even to the extent of falsifying the census figures. These are today’s commonplace facts. Among other revelations, you may visit the memoirs of a then serving British colonial officer, Harold Smith. I did meet that author, by the way, quite a few times. His revelations have also been corroborated in recent times by highly placed British officials,” he added.

Soyinka explained that these were among the reasons why many of “us have been saying: Let’s admit that costly mistakes have been made, let’s correct them now by restructuring. Some use the word reconfiguring. Others settle simply for socio-political rearrangements. It all boils down to reformulating the protocols of association; the relationships of the parts to the other parts. Of the parts to the centre, reducing the powers of the centre. Decentralising, pushing the envelope of state or regional autonomy as far as it can go without actually bursting it.

“Time to really sit down and tackle this reformative agenda and then proceed in that now inevitable decentralisation direction; creating even healthy rivalry which can only take place with larger degrees of autonomy. Stop this untidy business of going to the centre with a beggar’s bowl in hand and then struggling for the sudden windfalls which come from outside to this centre-forgiveness of debts and things like that. Rather, get the federating units to negotiate their economic priorities both internally and outside.

“We must be bold enough. We shouldn’t shy away from what I call a frank national Indaba in which representatives of various interests across professions, across religions, across states and ethnic groups come together. I don’t care whether it lasts three months in which we abuse, insult one another, enter into recriminations, give examples of how this happened, why should this still happen? An exhaustive Indaba in which we get out of our systems all these issues we’ve been papering over, sweeping under the carpet, failing to recognise that the destructive power of an accumulation of these little bits of frictions, sometimes unforgiven and unforgivable acts of hostility, between the units that are still there, simmering. You bring them out and ask, how do we go about closure? And from there we proceed to re-examine the protocols that supposedly bind us together.

“In other words, fashion a new constitution. It’s both therapy and common sense to leave the ghosts of the past behind. An Indaba whereby we admit what we did, that is, what the Federation of Nigeria did to a seceding unit like Biafra. Biafra too will have to admit what she did to some of the minorities in her midst who still have not forgiven Biafra. In which we even, if we like, talk about the various coups–-how this happened, why it happened. Some may believe that this will create greater friction and division. I don’t think so. I think years have passed and numerous other routes have been taken which have not brought us anywhere near closure. Perhaps an element of risk is involved, I might admit it, but I think keeping silent is worse.”

According to Soyinka, Something similar was the Justice Chukwudifu Oputa-led The Human Rights Violation Investigation Commission of Nigeria but noted that it didn’t go far enough and that there was far too much legalistic dance-around where lawyers literally took over.

He said the Commission was enabled to fail as it was dramatic in some instances, but that one of the problems there was that it became a ‘lawyering’ parade in which everybody wanted to show how clever or cunning they were.

“A people’s Indaba, that’s what I am talking about. At that Indaba, we will also pillory those who allowed religious bigotry, and its attendant violence, to take root. If they want to deny it, some of us who are living witnesses, those of us who warned them at the time, will demand of them of why they chose not to stop it at the critical time. Once you allow one constituent state to declare itself a theocratic state, you have opened a Pandora’s box, the contents of which will consume and destroy the nation. They knew it all, so they poo-pooed wise counsel. We said, don’t let it happen, don’t let theocracy have even a toe hold in the nation. Tell the theocracy-mongers they must be content with the existence of the existent systems of laws, like native laws and customs, which allow for civil settlements under the existing codes of cultural arbitration-nobody ever quarrelled with that.

“But when you have a situation where a crime somewhere is exemplary conduct next door, where, when you move from one state to the other, you come under the arbitrary jurisdiction of that other state where something which will not earn you the chopping of your hand, now brings about that particular forfeit, then you do not have a state–you have several states in one. We know those who were responsible for what we endure today. How many years ago was it that Goodluck Jonathan was being urged to make a move against Boko Haram? We heard Muhammadu Buhari countering with the declaration that any move against Boko Haram was a move against the North until he himself came under fire and nearly lost his life.

“We are talking about fundamental human rights, the right to congregate in pursuit of your form of worship, to believe or not believe, individual rights, collective rights of worship, etc., etc. But there are those for whom religion is merely an avenue for domination. I am talking, once again, about power and freedom. History actually spins on that axis of power and freedom. Most clerics are merely beneficiaries of being on the side of power and domination over their flock and their extension into society.

“They are not more pious than any member of their followers, and that is one realisation they refuse to confront. That’s why it is so difficult to exterminate Boko Haram completely: they have tasted power, they relish power, and they are still enjoying power. They enjoy being able to thump their noses at secular authority. They kidnap our children and turn them into slaves –it is their gesture of contempt for you and me,” he stated.

-

news7 years ago

news7 years agoOsun Government presents 2015, 2016 audited accounts…sets record as the first state in Nigeria to publicly declare accounts

-

crime5 years ago

crime5 years agoArotile’s ex-classmate had no driver’s licence, report reveals

-

lifestyle8 years ago

lifestyle8 years agoAmazing Tips for an Outstanding Makeup

-

news4 years ago

news4 years ago2023: Kola Abiola Set To Declare For Presidency

-

entertainment5 years ago

entertainment5 years agosanwo-Olu honours sacked chaplain after Ambode’s wife saga

-

entertainment6 years ago

entertainment6 years agoSee how Women now use toothpaste to tighten vagina

-

lifestyle5 years ago

lifestyle5 years agoUS Church ‘refunds members three years tithes’ as help during COVID-19

-

business4 years ago

business4 years ago#EndSARS: Access Bank announces N50 billion interest-free facility for businesses